|

|

|

|

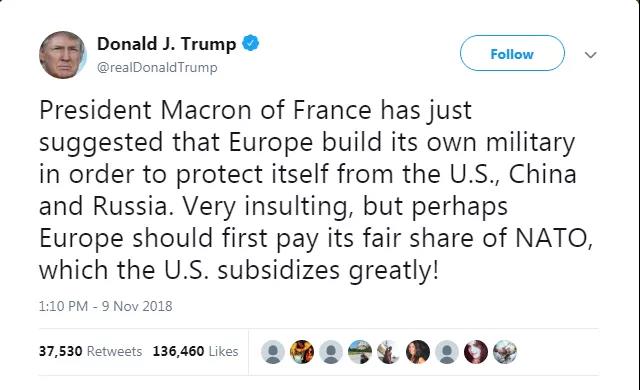

It was reported earlier this week that French President

Emmanuel Macron suggested Europe should "build its own

military in order to protect itself from the US, China, and

Russia". This claim enraged American President Donald

Trump, who soon angrily tweeted “very insulting” as a response.

However, the latest news shows that Trump and Macron have

reached an agreement on Saturday involving issues of increasing

European defense spending and related security affairs. As

international public opinion suggested, this conduct is expected

to paper over the embarrassing trans-Atlantic dispute. But does it

really work?

Europe's Dream of Building an Autonomous Defense

Rome was not built in a day; it is the same with the trans-Atlantic

tension and resentment. This seemingly accidental event actually

has a much deeper root in the long history of trans-Atlantic

relations.

After World War II, the US rebuilt ruined Western Europe through

the Marshall Plan. Years later, the US military force integrated

Western European defense through the framework of NATO as a

strategic response to the escalating Cold War against the

Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact.

From then on, Western Europeans enjoyed the privilege of

“free-riding” in security that maintained a high level of

collective security at a relatively low cost.

However, there is no such thing as a free lunch. Saving military

expenditure under the US nuclear umbrella constrained the

strategic and political autonomy of Europeans.

When the two sides across the Atlantic Ocean shared the same

strategic goal in front of a common enemy, such as the Soviet

Union at the height of the Cold War, the impulse of defense

independence was covered.

But when the common foe collapsed and the Cold War ended, a

growing determination of military autonomy emerged; and the

EU, which aims to play a more provocative role in both global

and regional affairs, began to call for larger discourse power within

NATO.

If these demands aren't met, it is reasonable for European leaders

to call for a “real European army” to protect themselves from

external threat. This long evolving history constructed the deep

background of the Trump-Macron Twitter War.

Macron's 'Insult': The Beginning of a Bitter Trans-Atlantic

Divorce?

Before commemorations to mark the 100th anniversary of the end

of World War I, Macron welcomed Trump under “rainy Parisian

skies with a firm handshake…But there appeared to be less

immediate warmth in the greeting between the two than in the

past.”

CNBC's vivid description of the weather and meeting details

has set the atmosphere of this visibly reluctant reconciliation

performance: Seated on gilded chairs in the ornate

presidential palace, Macron placed his hand on Trump's knee

and referred to him as “my friend,” while Trump kept more

distance, although he also talked up common ground on an

issue that had caused friction.

However, beyond analyzing the ritual elements of this event,

it is still hard to predict an immediate “divorce” between

Europe and America. The process and interactive results may

depend on the two sides' costs-benefits calculation of various

“strategic asset portfolios,” as well as considering related

security and political risks.

For the EU, they have to make a choice between running a highly

independent and autonomous defensive system at a much higher

financial cost and maintaining the current collective security system

and regimes that enjoy economic benefits with the disadvantage

of bearing the American changing moods and bad temper.

Key internal and external elements that may change

European strategists' calculations include but are not limited to:

(1) Trump's bargain and “price making”: To what extent of

the portion that Trump urges the EU to bear NATO's military

expenditure;

(2) US “threat”: In the EU's perspective, the US does not pose

an actual direct military threat (such as invasion, territorial

annexation, etc.); however, the Trump administration's

abuse of the US' arbitrary power has insulted and

weakened the EU's collective sovereignty as a whole.

And the US military's adventurism and consequent military

catastrophes in regions around Europe (such as the Middle

East) have created a lot of (non- traditional) security and

social problems for Europeans, including but not limited

to refugees, terrorism, social division, the reactive trend of

rising far- right parties in EU member states, and so forth.

(3) Third-party threat: When the threat from a third party

(e.g. Russia) decreases (in other words, their bilateral relations

are promoted), there will be less necessity for the EU to

enhance its defensive force, and hence, less motive and

demand for expenditure.

Therefore, the EU may be satisfied with a new option that

maintains a smaller but more independent-autonomous

defensive system. This situation requires a general

reconciliation between the EU and the targeted “third party,”

which may serve to cripple the US military existence in Europe.

What option will US and EU leaders choose eventually?

Where is this nearly a-century-long trans-Atlantic

“marriage” going in a Trump era of uncertainty? May bitter

time and tougher bargains tell the story.

Copy Editor/ Kang Sijun

Editor/Kang Sijun

来源:察哈尔学会

WANG Peng